From the roaring metals markets of the 1930s to the recent surges in battery minerals, commodity supercycles shape economies for decades. Understanding these extended trends empowers investors, policymakers and businesses to seize opportunities and mitigate risks. This article explores the defining features, historical lessons, current signals and practical strategies to navigate the next grand wave in global resources.

A commodity supercycle is a decades-long period during which prices of a broad basket of resources—from metals to energy and agricultural goods—persistently exceed their long-term averages. Unlike typical market swings lasting two to five years, supercycles often span 10–20 years, reflecting slow-moving changes in supply and demand.

These phases involve simultaneous booms across multiple commodities, driven by structural forces such as urbanization, population growth and technological breakthroughs. The delayed response of supply—new mines or wells may take seven to ten years to come online—fuels extended rallies and sets the stage for dramatic busts when capacity finally catches up.

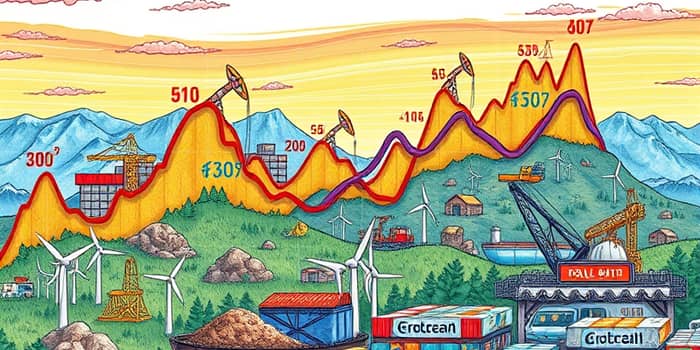

Historical supercycles offer valuable insights into how resource markets evolve and impact global prosperity. From the copper boom during post-Depression rebuilding to the oil shocks of the 1970s and China’s industrial surge in the 2000s, each cycle has unique catalysts and legacies.

The 1970s episode, triggered by embargoes and rising consumer demand, saw gold climb from $35 to over $800 per ounce. The early 2000s cycle, led by China’s urbanization, drove annual commodity demand growth of 15–20% at its peak. Each boom created generational wealth opportunities for resource-rich nations and savvy investors, but also left economies vulnerable when prices collapsed.

Understanding what fuels supercycles helps anticipate their phases and manage exposures.

For example, global mining exploration capex fell by nearly 60% from $29.4 billion in 2012 to $11.2 billion in 2024, setting the stage for potential deficits in copper (an 8 million-tonne shortfall by 2030) and uranium (meeting only 74% of current needs).

Supercycles reshape economic landscapes. Exporters—such as Australia, Brazil and Canada—see windfall revenues that fund infrastructure, healthcare and social programs. At the same time, import-dependent countries face inflationary pressures and policy dilemmas when prices soar.

Investors experience wild profit potential in mining equities, commodity futures and ETFs during booms—but must also weather sharp downturns. The natural gas price leap of 69% in Q3 2021 or oil’s 300% surge from April 2020 to late 2022 illustrate how quickly fortunes can change. Companies that planned expansions during peak prices often confront low returns when markets reverse.

As of late 2023, the CRB/S&P 500 ratio hit 0.15—near a 50-year low preceding the 1970s bull run. Combined with supply chain disruptions, geopolitical tensions and lingering persistently low inventories, some analysts argue these conditions mirror the early stages of a fresh supercycle.

Metal prices rose by 48% in 2021, coal by 44% and agricultural commodities by 22%. Ongoing underinvestment in mining and the push for electric vehicles may further tighten markets for copper, nickel and lithium. Yet skeptics point to temporary, pandemic-driven shocks, warning that short-term volatility does not guarantee a decades-long upswing.

By combining macro awareness with disciplined risk management, investors and companies can capture upside during booms and preserve capital in busts. Policymakers, too, can use sovereign wealth funds and stabilization mechanisms to smooth revenues and avoid the so-called “resource curse.”

The global shift to electrification and renewable energy may define the next supercycle. Demand for clean energy and green infrastructure hinges on metals like copper (for wiring), nickel and manganese (for batteries), and rare earths (for wind turbines). Forecasts suggest a sixfold increase in battery metal demand by 2035, a surge that could outpace supply growth without significant new investment.

Governments and private firms racing to secure extractive and recycling capacity will play a pivotal role. Strategic partnerships, streamlined permitting and targeted R&D could ease bottlenecks, while environmental and social governance standards ensure sustainable development.

Commodity supercycles offer both promise and peril. Their multi-decade arcs are shaped by forces beyond quarterly earnings, demanding long-term vision. Whether you are an investor, corporate leader or policymaker, embracing adaptability, data-driven insights and prudent risk frameworks will be your greatest asset in navigating the next great wave of global resources.

References